Experiences with production support, Part 2: Ask questions

Starting at the beginning

The most obvious question to ask when being called out is “what’s wrong?” And Hopefully someone or some report can give you guidance on what is happening. This usually turns out to be a symptom of the problem, however. Normally something else is going wrong.

It can be difficult for users to know what the real issue could be in any given situation. Users just tell you what is happening to them, they don’t always have the full picture. They’re also probably in the middle of trying to get something else done, and can become frustrated because instead of enabling your user, you are now actively hindering them.

“One of the first things taught in introductory statistics textbooks is that correlation is not causation. It is also one of the first things forgotten. - Thomas Sowell”

Asking questions as a diagnosis tool

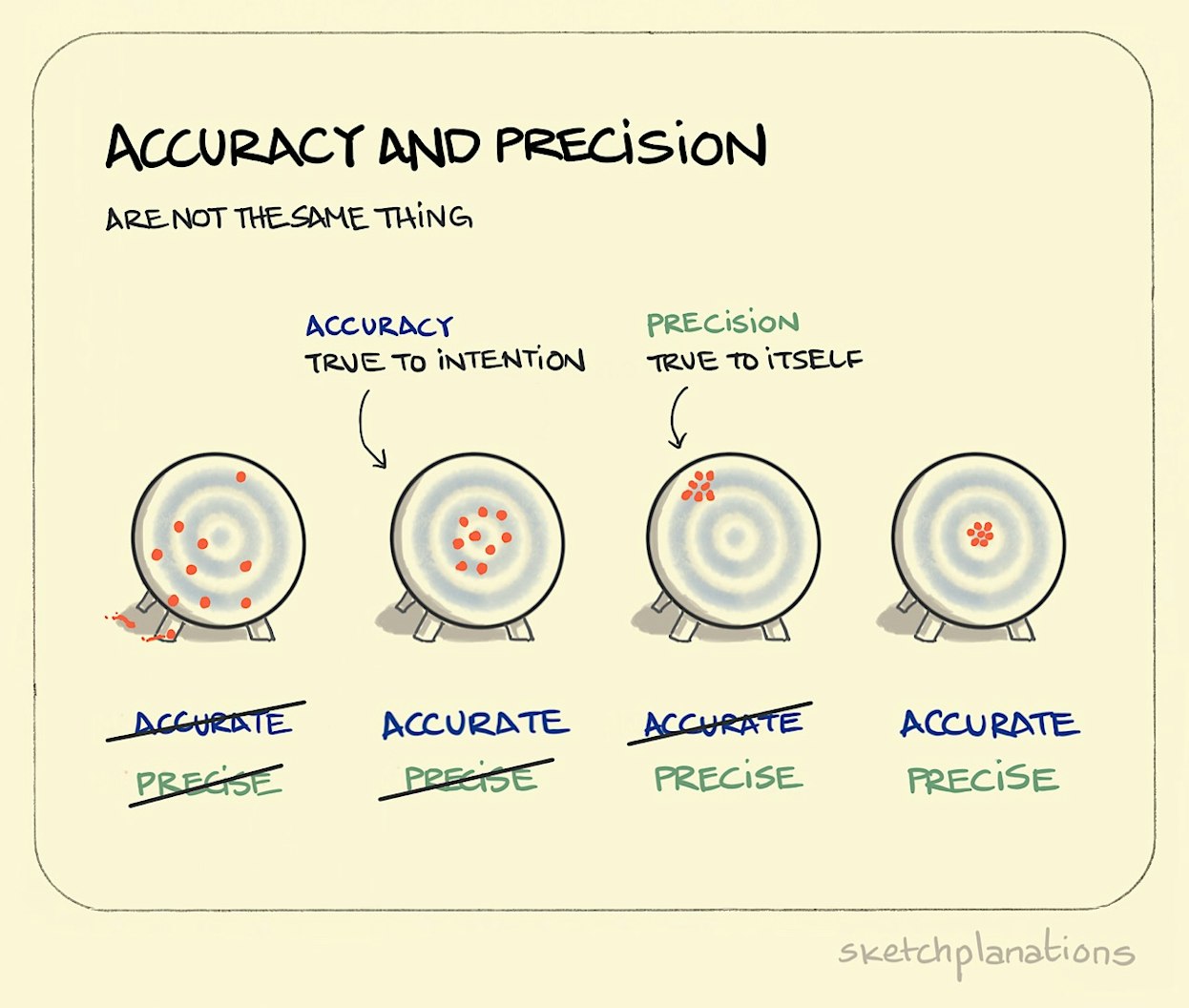

When I first started getting called out, I put all the weight of discovering the issue on my shoulders. I would hastily try to point the finger at some service to get it fixed as soon as possible. I was so afraid of reputational damage from being down 1 more second that I would be clamouring to find the issue. The problem with this approach is it’s like throwing all the darts at a dart board without aiming. You lack both precision and accuracy.

What I have found helpful is to talk to the team as I make discoveries about systems that may be problematic. I ask questions in the hopes of guiding a conversation. For example: “I have noticed system A is doing garbage collection every 10 minutes, and during the collection that is when our users are experiencing lag - could that be causing the problem?” This goes a long way in terms of being helpful and not diverting everyone’s attention all the time.

One time we were on a call out where it really looked like the core transaction system was refusing to allow the happy path through. We all insisted that the problem lay with the transaction service, until we found out that the authentication section of the flow was actually responsible, and therefore further up in the chain. Not only were we wrong, but we had been causing the rest of the team to focus in the wrong area.

If you come out sounding like an expert on something and it turns out you’re wrong, it’s very difficult to come back. Rather ask questions and be a part of a guided conversation than be ignored for constantly crying wolf. Just remember during a call out you have your own reputation to maintain.

Another important aspect of communication on a call out is that of domain understanding. You cannot be expected to know everything about an ever-changing always-increasing domain space. The best approach I have found is to accept when something is unknown and just ask.

I remember once being told there was a problem with AOL. I was so confused because it was 2015 and a South African financial institution. Why were we running critical features on America On-Line? Did they even do that kind of thing? After 30 wasted minutes eventually I backed off and asked what AOL meant in their vocabulary. It was an internal service that had been coined “Accounts On Line.”

Another question to ask is “What caused the call out?” Normally this gives an indication of where to start looking, or at least how to reproduce the issue. I normally group them as follows:

- Social media / Call centre complaints - some experience is being affected and is more likely a subset of devices (e.g. Samsung Android devices) or a downstream service could be slow.

- Historic baseline delta spike - normally these are anomalies, like people doing more or less transactions during Christmas or New Years.

- Management personal account - sometimes a high level manager with a production account will report a problem to the support team. These are normally a personal connectivity issue.

- Crash rate increase - these are the most concerning as there is usually something really serious going on.

In any case, all of these tell you something, and all information is useful in the diagnostic process. The worst mistake you can make, however, is assuming nothing is wrong because of the source of the complaint. Always do your due diligence.

Separate concerns

As an Android engineer whenever I get told the app is failing, the best first question I can ask is: “Is it failing on iOS and Desktop as well?” I have tried to explain the benefits of this approach to testers that I have worked with over the years.

If there is a dependency that is causing an issue, the issue will appear on all systems, but if the issue is solely on one platform that share that dependency, then it’s safe to assume the platform itself has a problem. I have found this question to be one of the most helpful “first questions” I can ask. However, if you have a hybrid app it can muddy the waters, since they both use the same code base, but are executed on different platforms. It has happened multiple times that Cordova has encountered a rendering problem on a very specific platform, and we were convinced it was the code.

Reproducing the issue is probably the easiest way of getting to the bottom of a problem. I have had experienced QA’s tell me the app is crashing when all it was doing was reporting an error. Clarifying steps to reproduce is extremely important and can be very tricky. I have had people tell me they open a screen and then go back, and I assumed that they waited for loading to complete before going back, only to find hours later that they didn’t wait for it to load, or they were in a specific orientation. It’s always best to be able to reproduce first before assuming you know what the issue is.

Once a manager hit the panic button because they were looking at DownDetector.com and thought there was an issue. It turns out a popular network was down and had a waterfall affect on our baseline on the site.

Look around

Knowing what is going on in a complex architecture can be difficult, so it’s really important that systems have documentation associated with them. We found it particularly helpful when we could access the release notes of different systems and find out when changes were made. The most typical question to ask when something that was working starts the fail is: “why now?” - What was the most recent change and could that have been the cause?

However there will be times when the problem is not internal or even a third party system. Every time Samsung does an update, or a new phone gets developed, you have a new support criteria to consider. Understanding fragmentation beyond just the scope of Android is very important.

Determine the impact

While on a call out, it’s really important to remember that at the end of it the business is going to want to understand the impact. To both themselves and the customers. Gather data and always be trying to answer this question as you go. I normally try to keep the following in mind:

- Root cause: what actually caused the problem?

- Feature affected: what did users see?

- Reports:

- how did we know something was wrong?

- how do we know it is fixed?

- Users affected: can we determine the total number of unique affected users?

- Downtime: how long did it last?

- Resolution: what did we do to fix it?

- Reflection: how would we do it differently?

Comments

No comments found for this article.

Join the discussion for this article on github. Comments appear on this page instantly.