Practical Patterns: Adapter

One of the biggest cause of delays in software development is that of dependencies. It seems as though we’re always waiting for something - designs, copy, data, decisions. However time spent waiting is time wasted. Especially when it comes to data.

I remember as a third year student, we had to develop a system for a bank. The bank could afford to wait to give us test data, but we couldn’t. We only had a very specific time frame and eventually (after two weeks) we realised we needed to make it up ourselves. We never did get that data, and we lost a lot of precious time as a result.

The above experience is my first memory of dependency hell. The odd thing is, even 16 years later I still see it quite often. Teams and software delayed because of some other part of the entire system. I think the worst thing one can do, however, is simply wait for the situation to change.

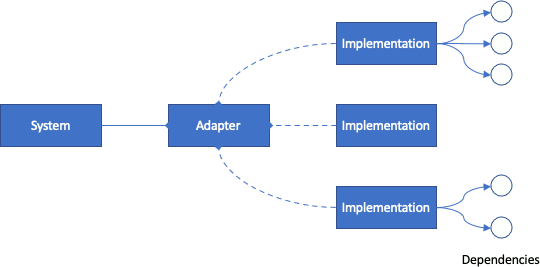

Enter the adapter pattern. This structure allows developers to define an interface, that when implemented, uses a specific component. This may sound a lot like a simple contract, but knowing what you are doing is the key element.

Sometimes the problem can be an unknown or unavailable data source. Projects may require tracking some sort of sensory data obtained from another system. This could be a temperature sensor out in a field, or GPS coordinates from a tracking device. Either way, when writing a system that depends on incoming data, it is tempting to start at the data source. Instead you could start by creating the interface that you expect the underlying system to implement, and then implement a rudimentary one that returns some static data.

interface GPSTracker {

fun subscribeToUpdates(onCoordinateReceived: (x: Float, y: Float) -> Unit)

fun unsubscribe()

}What I like about this kind of approach:

- There is no doubt about the purpose of the interface

- The name is clear, and it encourages implementations to have meaningful names

- Dependency isolation

- abstraction from domain-specific implementation

- tests can be written on one component at a time

- implementations can be modified easily

- Data control

- Use build variants to hide implementations from each other

- If a component has a predictable dependency, it’s tests will be reliable

- Fast development

- Bypass secondary requirements like login - logging in for every build is a time-waste

- Focus on the task at hand

- No dependency injection (yet)

Consider the most basic example, which runs on the main thread and uses a simple data set:

class StaticGPSTracker : GPSTracker {

data class TestPoint(val x: Float, val y: Float, val sleepMillis: Long)

var subscriber: ((x: Float, y: Float) -> Unit)? = null

private var index: Int = 0

private var points = listOf(

TestPoint(1F, 1F, 300),

TestPoint(2F, 2F, 250),

... //You get the idea

)

override fun subscribeToUpdates(

onCoordinateReceived: (x: Float, y: Float) -> Unit) {

subscriber = onCoordinateReceived

publishNextCoordinate()

}

override fun unsubscribe() {

subscriber = null

}

private fun publishNextCoordinate() {

index %= points.size //ensure wrap

subscriber?.apply {

this(points[index].x, points[index].y)

Thread.sleep(points[index++].sleepMillis)

publishNextCoordinate()

}

}

}

...

class MainActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

private val tag = MainActivity::class.java.canonicalName

private val gpsTracker: GPSTracker = StaticGPSTracker()

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main)

gpsTracker.subscribeToUpdates(::onCoordinateReceived)

}

private fun onCoordinateReceived(x: Float, y: Float) {

Log.d(tag, "COORDINATE: [$x,$y]")

}

}While simple enough, the example above is sleeping on the main thread, which is not recommended for long running or ongoing underlying operations. Other solutions might involve the deprecated Handler class, however we can create a new version with coroutines. This doesn’t change the Activity’s behaviour, it just uses a different instantiation of the same interface.

class StaticCoroutineGPSTracker(private val scope: CoroutineScope) : GPSTracker {

var subscriber: ((x: Float, y: Float) -> Unit)? = null

private var job: Job? = null

private var index = AtomicInteger(0) // Because threads

private val points = testPoints // Moved to separate file

override fun subscribeToUpdates(

onCoordinateReceived: (x: Float, y: Float) -> Unit) {

job?.cancel()

subscriber = onCoordinateReceived

job = scope.launch {

withContext(Dispatchers.IO) { // ensures running on separate thread

publishNextCoordinate()

}

}

}

override fun unsubscribe() {

job?.cancel()

subscriber = null

}

private fun publishNextCoordinate() {

subscriber?.apply {

val position = index.get()

scope.launch {

withContext(Dispatchers.Main) {// Back on the main thread

this@apply(

points[position].x,

points[position].y

)

}

}

Thread.sleep(points[position].sleepMillis)

// wrap

index.set((index.incrementAndGet()) % points.size)

publishNextCoordinate()

}

}

}

// making the MainAvtivity use:

// private val gpsTracker: GPSTracker = StaticCoroutineGPSTracker(MainScope())This is all the power of the adapter: Being able to swap out behaviour without affecting the rest of the system. It’s at this point we could dive into dependency injection, permission management (if we want the data from the devices sensors) or start creating a web API for downloading data. What has been achieved is demonstrating that listening for a collection of GPS coordinates does not mandate those dependencies.

It’s at this point that I started to want to put this on an actual map, but I ran into another dependency! The Google MapView has quite a lot of boilerplate and work that requires implementation, plus an API key that needs to be obtained. This is all fine and good, except now there is a part of the code that needs to be my secret (i.e. not available to developers who download the example code), and also means that I can’t use something else like MapBox or Nokia Here. When there are this many options for providers, we have the perfect makings for an Adapter. So I did that.

The first thing I did was make a simple View (SomeMapView) to render something that resembles a map. It inherits from FrameLayout in the same way that Google maps does. The important part, however, is the idea that we can place a pin on the map somewhere. And so I created my adapter:

interface MapMarkerAdapter {

fun placeMarker(x: Float, y: Float)

}

...

class SomeMapView(context: Context, attrs: AttributeSet)

: FrameLayout(context, attrs), MapMarkerAdapter {

private var pinX: Float = 0F

private var pinY: Float = 0F

...

override fun placeMarker(x: Float, y: Float) {

pinX = x

pinY = y

invalidate()

}

...

}

...

// Back in the activity

private fun onCoordinateReceived(x: Float, y: Float) {

(mapView as MapMarkerAdapter).placeMarker(x, y)

}The map implementation details do not matter. Where the points come from do not matter. Developers need to remain focussed on the task at hand. And when it comes time to plug in a particular dependency, they need to implement a very simple interface. As long as the view object inherits from the MapMarkerAdapter the placeMarker method can be called. Any other behaviours are side effects to the goal. The results are quite satisfying:

What was avoided?

- Permission management is separated out

- Data source is separated from implementation logic

- Map SDK agnostic - no need to decide which map provider to use (or spend time learning it)

- No internet permission needed

- Very little reactive programming (one delegate)

- Data representation is abstracted

- Platform-agnostic solution

- Dependency Injection can be better defined knowing exactly what the dependencies beforehand

I hope that thinking in terms of dependencies and adapters will help developers create great software, and enable the right type of focus. I often use the adapter pattern when I don’t have a data source like a web API up and running, or if there is some login process I need to go through in order to fetch data. It’s really useful in Android because if a build variant is used, then the test code never gets compiled in the actual release.

If you would like to see / download the code used in this blog, you can find it here.

Comments

No comments found for this article.

Join the discussion for this article on github. Comments appear on this page instantly.